| [http://elc.polyu.edu.hk/Conference/elclogos.htm] |

|

[http://elc.polyu.edu.hk/Conference/polylogo.htm] |

Information Technology & Multimedia in English Language Teaching

Navigation: ITMELT Conference Home Page > Abstracts > Papers > .

Evaluating five speech recognition programs for ESL learners

Hao-Jan Howard Chen

Foreign Language Division

Department of General Education

National Taiwan Ocean University

Keelung, Taiwan

Introduction

As personal computers become more powerful and affordable, they are becoming more

attractive as tools for foreign language teaching/learning. More and more teachers and

learners are increasingly interested in computer-assisted language learning (CALL)

programs. Recently, many companies have incorporated speech recognition technology into

their products which they claim can facilitate the development of listening and speaking

skills. Although the programs featuring speech recognition technologies seem quite

attractive, it is necessary to examine these programs more closely before they are

adopted.

This paper uses a set of evaluation criteria based on second language acquisition (SLA)

theory to examine the usefulness for learners of English as a Second Language (ESL) of

five CD-ROM programs which use speech recognition technology.

Chapelle's Evaluation Criteria for Multimedia CD-ROMs

Teachers and learners lack clear evaluation guidelines and find it difficult to decide

which programs in the wide range of multimedia CD-ROM titles available for English

teaching and learning are useful. However, most existing evaluation guidelines are based

on general educational theories or theories of computer-human interaction. Few take into

account theories of second language acquisition or foreign language learning. To overcome

this problem, Chapelle (1998) collected together, from other authors, a set of seven

criteria for evaluating CD-ROM titles based on SLA interactionist theory. The criteria

express conditions to be met by good programs. They are:

1. The linguistic characteristics of target language input need to be made salient

(Doughty, 1991).

2. Learners should receive help in comprehending semantic and syntactic aspects of

linguistic input (Larsen-Freeman & Long, 1991).

3. Learners need to have opportunities to produce target language output (Swain,1985).

4. Learners need to notice errors in their own output (Swain & Lapkin, 1995).

5. Learners need to correct their linguistic output (Swain, 1998).

6. Learners need to engage in target language interaction whose structure can be modified

for negotiation of meaning (Long, 1996).

7. Learners should engage in L2 tasks (goal-oriented two-way communicative tasks) designed

to maximize opportunities for good interaction (Pica, Kanagy, and Falodun, 1993).

According to Chapelle (1997, 1998, 1999) and Chen (1999), some of these conditions are met

by many good CD-ROM titles. For instance, many programs highlight the key words or phrases

in a lesson by using special fonts or colours. These programs are expected to provide

enhanced input to language learners. In addition, CALL programs provide many different

options for learners to achieve better comprehension. For instance, some programs provide

simplified or annotated readings or listening materials recorded at a slower speed.

Moreover, online references such as dictionaries or grammar notes are also provided.

Comprehensible output and corrective feedback are less well supported as many CALL

programs can only elicit limited written output from learners (via multiple choice and

blank-filling tests) and learners rarely have opportunities to write complete sentences.

Because output opportunities are limited, corrective feedback only focuses on certain

targeted linguistic items or structures. Most traditional CALL programs are unable to meet

Chapelle's conditions 3, 6 and 7.

Speech recognition technology may improve the ability of CALL software to provide

corrective feedback thus creating beneficial language learning conditions. This paper

examines five commercial software packages featuring speech recognition technologies in

order to compare facilities offered and find examples of the best practices. The programs

are briefly introduced, their speech recognition capacities are examined and their

strengths and limitations in helping ESL/EFL learners develop better speaking skills are

discussed.

Five CD-ROM programs featuring speech recognition technology

The five pieces of software compared in this paper are: Caroline in the City/CNN

Interactive English (Hebron Soft), Syracuse English Comprehensive Learning Series

(Syracuse Language), TeLL Me More Pro (Auralog), TRACI Talk (CPI), and Encarta Interactive

English Learning (Microsoft).

Caroline in the City / CNN Interactive English

Caroline in the City was created specifically for Chinese learners of English. The content

is taken from a very popular CBS TV comedy show called Caroline in the City. The program

focuses mainly on developing listening and speaking skills. It combines full screen video

and a wide range of powerful learning tools. Learners can manipulate the video extensively

and can request monolingual or bilingual subtitles at any time. They can view the complete

program scripts or practise any word/phrase used in the show by using the comprehensive

glossary. Grammar notes and quizzes are also available.

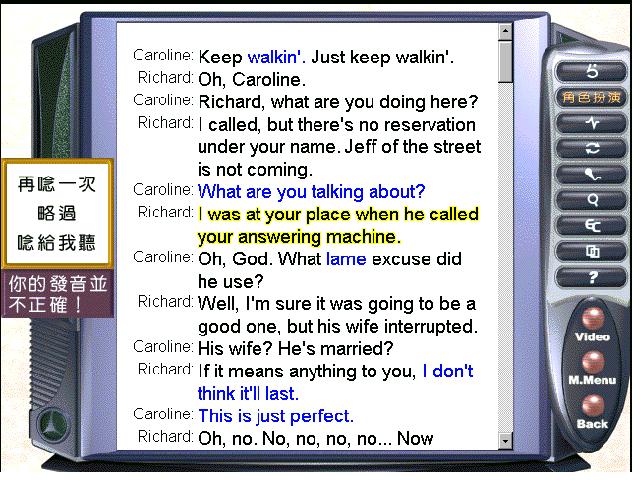

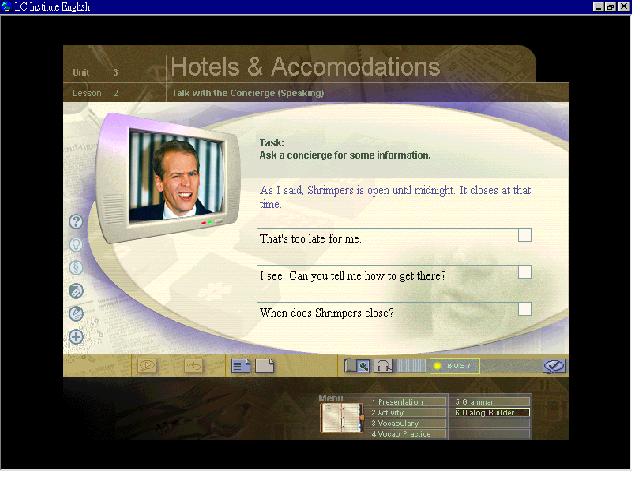

Speech recognition technology is used in role-play activities (Figure 1) where learners

choose a role from the show. They read their dialogue (shown on the screen) to the

computer which uses the Microsoft Speech Recognition Engine to evaluate their output and

give them feedback. Learners can try again, skip a sentence, or ask for modelling when the

recogniser does not accept their output.

The settings of the speech recognition engine in this program can be misleading. Although

learners can adjust the sensitivity of the speech recognition engine, if it is adjusted

too high, few sentences will be accepted and if adjusted too low all sentences will be

accepted. The program does not specify clearly what level is suitable for learners which

could lead to a distressing learning experience.

Figure 1: The role-play activities in Caroline in the City

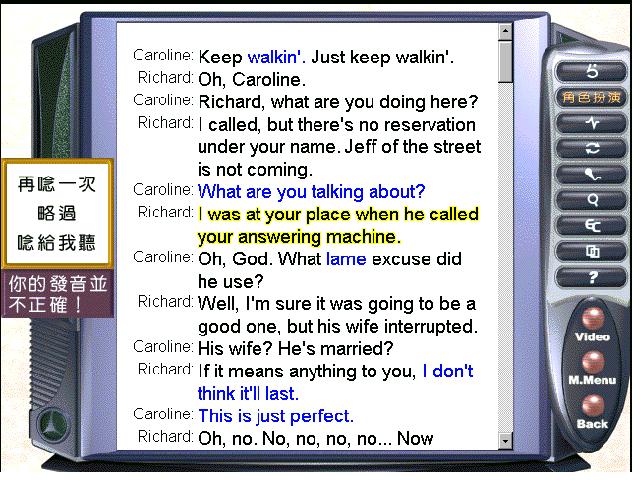

The successor to Caroline in the City, CNN Interactive English is similar although it

allows learners to record their voice and compare it with a native speaker using an

on-screen voice (Figure 2). However, it is doubtful whether second language learners can

really improve their pronunciation and intonation by examining the speech spectrum. As

indicated by Ehsani & Knodt (1998), researchers have not yet provided clear

experimental evidence for the effectiveness of this type of visual feedback. They suggest

it should be presented with other types of feedback and with instructions on how to

interpret the displays.

Figure 2: The voice spectrum in CNN Interactive English

Syracuse English Comprehensive Learning Series

The Syracuse English Comprehensive Learning Series (Syracuse Language) has 7 levels but we

will concentrate here on levels 4 to 7 which focus on developing the four language skills

with college level students. The key learning activities and tools include: video role

play (using the IBM Speech Recognition Engine), interactive conversations, listening

comprehension, reading and writing, vocabulary, grammar, cultural notes, record/playback,

and an English dictionary.

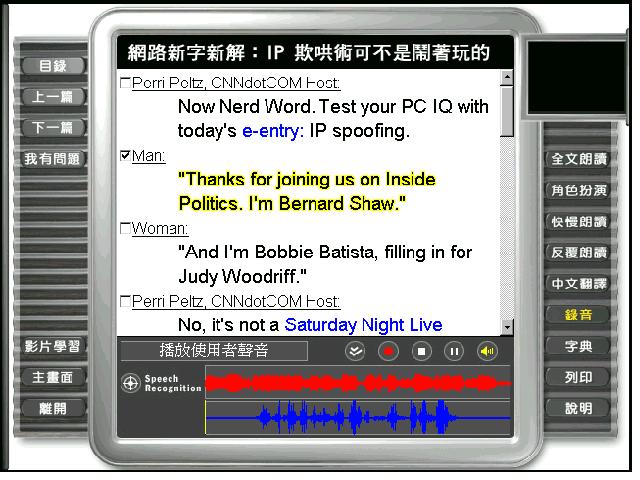

In the role-play activities (Figure 3), learners first watch a video of a conversation and

then play a role in the conversation. They then record their lines of the conversation

during which the speech recognition engine evaluates the quality of their pronunciation

and intonation. If unacceptable, they are asked to try again. During experimentation the

speech recogniser proved mostly reliable by accurately distinguishing between the clear

and unclear utterances of ESL learners.

Figure 3: The role play activity in the English Comprehensive Learning Series

Another activity engages learners in a dialogue. After listening to an electronic

conversation partner, learners choose an appropriate response from three on-screen options

which they read aloud to the microphone. Acceptable answers cause the conversation partner

to smile and continue the conversation. Unacceptable answers cause a puzzled face and

repetition (Figure 4).

Figure 4: A response to an inappropriate answer

TeLL Me More Pro

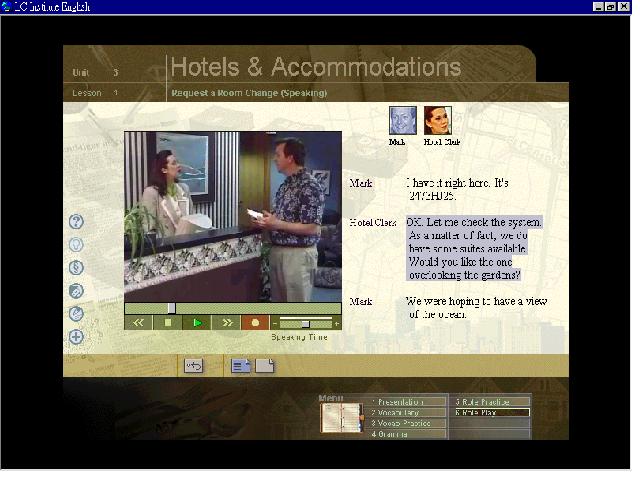

In TeLL Me More Pro each lesson follows the same format. Lessons are based on video scenes

and include an interactive dialogue, a pronunciation practice, a comprehension activity

and a range of additional exercises which support vocabulary and grammar structure

acquisition.

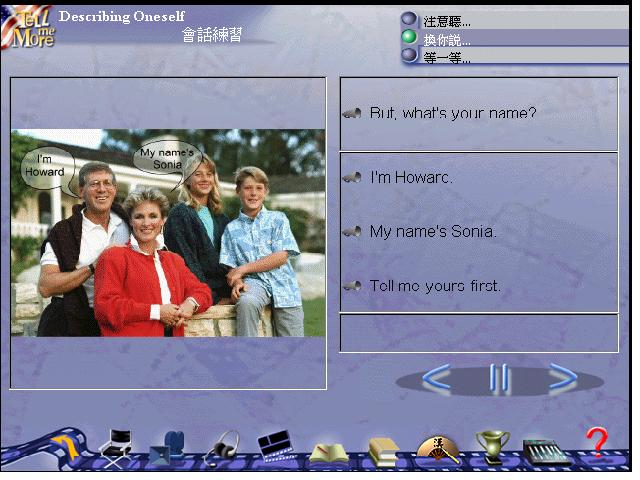

In the dialogue mode of this program, learners first listen to the program then choose one

of three acceptable responses given on screen and pronounce it clearly into the microphone

(Figure 5). TeLL Me More acknowledges the response by highlighting it. The dialogue

develops according to the responses learners choose. If a response is not understood,

learners must try again. Like Caroline in the City, learners can adjust the sensitivity of

the speech recogniser. The accuracy of speech recognition in this program proved quite

reliable in testing.

Figure 5: A conversation with TeLL Me More Pro

In the pronunciation practice, learners listen to a selected word or sentence and then try

to reproduce it. The program scores the attempt by matching user input with the model

(Figure 6). Voice graphs and pronunciation scores are quite elaborate but no help is

provided to interpret. This is the kind of visual feedback that Ehsani and Knodt (1998)

suggest should be accompanied by other types of feedback and for which learners need help

in interpreting the displays. The educational value of this activity would be

significantly enhanced if learners could understand the meaning of the voice graph or why

their utterances do not match the model.

Figure 6: Pronunciation practice in TeLL Me More Pro

TRACI Talk

Perhaps the most well-known ESL CD-ROM program featuring speech recognition technology is

TRACI Talk. TRACI is an acronym for Teacher Ranging Across the Computer Interface which

represents the concept of a teacher within the computer who is available to help the user

whenever needed. TRACI Talk uses IBM VoiceType speech recognition and allows virtually

hands-free interaction with the computer. It is a highly interactive ESL/EFL program.

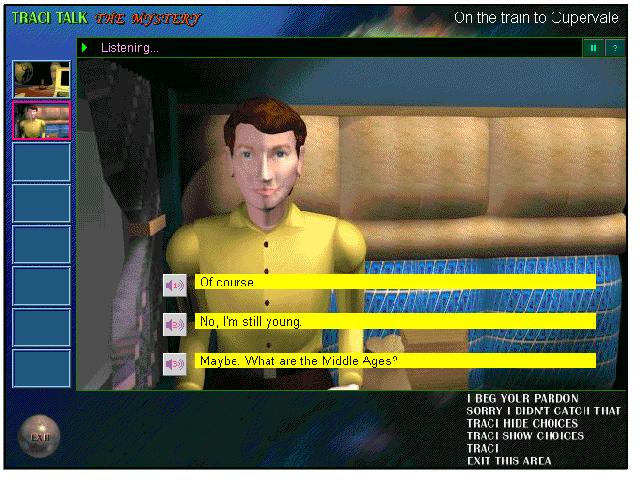

TRACI Talk allows learners to engage in a series of task-based conversations with

characters in the computer. Playing the role of detective, learners obtain information

from four suspects to solve an interesting and challenging mystery. Learners take their

turns in conversations by selecting and reading into a microphone one of three utterances

shown on the screen (Figure 7). Learners have opportunities for extended conversations

with the characters that can take many paths. This exposes them to a large amount of

natural and communicative English.

Figure 7: The options of response shown on TRACI Talk screens

As in real conversations, learners may ask for sentences to be repeated or rephrased, and

they need to steer the conversation to find out the answers to their questions. The desire

to solve the mystery motivates learners to listen carefully, speak clearly and keep asking

questions. Also learners may repeat entire conversations during which they can obtain

additional information by following different paths. When learners feel they know enough

about the characters, they can go to the next level by answering eight questions correctly

(taken randomly from a pool of 60). If they pass this test, they can invite the suspects

to their place for a chat and try to solve the mystery. If they do not pass the test, they

can go back to previous sections looking for more information or they can try to answer

another set of questions.

When tested on a range of computers, TRACI Talk's speech recognition engine performed

moderately well. The program processed oral input quickly and provided smooth interaction.

However, when input is inadequate, the program always responds with "Sorry, I do not

catch that, could you say again." or similar sentences. The feedback did not indicate

what was wrong with the input, not even making a distinction between pronunciation or

intonation errors. Thus learners cannot learn how to correct their mistakes. If the

feedback could pinpoint learners' weaknesses, the learning experience would be more useful

and pleasant.

Encarta Interactive English Learning

Encarta Interactive English Learning mixes several multimedia technologies such as video,

real-time 3D animations and speech recognition to immerse users in English. On first

starting the software, users create a profile which tracks their progress. Encarta

Interactive English Learning offers more than 360 different activities grouped into 10

units. Every unit contains listening, speaking, practice and vocabulary learning

activities, each of which offers learners a choice of exercise types. When a unit has been

completed learners take a Virtual Challenge which tests them on the main elements of the

unit.

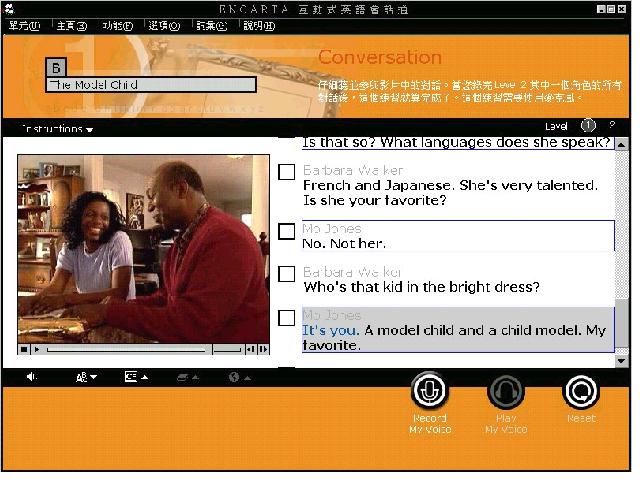

Speech recognition technology is used in the speaking activities and the virtual

challenges. In the speaking activities, learners play a role in a video segment. They

record their own voices after listening to a native speaker model (Figure 8) but the

program does not provide any feedback making it impossible for learners to know how well

they have performed.

Figure 8: Recording voice in the speaking activity of Encarta Interactive English

Learning

The Virtual Challenge provides a 3D virtual environment in which learners move around in a

virtual space and interact with the characters (Figure 9) who either question the learners

or provide them with useful information. Learners are also submitted to the same problems

or difficulties the characters encounter. This experience is intended to increase

interactivity and bring users into contact with the English language. The tasks (answering

questions, looking for other characters and talking with them, and finding objects and

bringing them back to specific locations) are challenging and fun. Navigation is easy so

learners will feel they are actually walking and talking in this virtual environment. This

is a motivating language learning environment.

Figure 9: The virtual challenge in Encarta Interactive English Learning

The performance and the judgement of the speech recognition engine in Encarta Interactive

English Learning are not impressive. In some cases any learner input is accepted although

in others the speech recogniser does have clear targets to match. However, when irrelevant

or improper utterances are made more than two or three times the program automatically

re-shows the relevant video segments (Figure 10). This clever intervention allows learners

to recall what they have learned earlier. The Virtual Challenge sessions in Encarta

Interactive English Learning require learners to produce language with no on-screen

prompts. This is challenging for the learners and also for the speech recogniser because

it has to be able to recognise a wide range of possible answers. This requirement might

sometimes reduce the accuracy rate of the speech recogniser.

Figure 10: The intervention during an interaction in the Virtual Challenge

Discussion

Ehsani and Knodt (1998) identify two fundamentally different system design types for

speech recognition: closed response and open response. In closed response systems such as

Tell Me More and TRACI Talk, learners must choose one response from a limited number of

possible responses presented on the screen. Learners know exactly what they are allowed to

say in response to any given prompt. By contrast, in open response systems like Encarta

Interactive English Learning, the possible responses remain hidden and the learner is

challenged to generate the appropriate response without any cues from the system. The

accuracy rate of open response systems is not as high as that of closed response systems.

Kenworthy (1987) and Eskenazi (1999) propose five basic principles that contribute to

success in computer-assisted pronunciation training situations.

1. Learners must produce large quantities of sentences on their own.

2. Learners must receive pertinent corrective feedback.

3. Learners must hear many different native models.

4. Prosody (amplitude, duration, and pitch) must be emphasized.

5. Learners should feel at ease in the language learning situation.

These principles can also be applied to assess the quality of the commercial programs

reviewed here.

Although all of the programs encourage learners to speak up and produce more

comprehensible output (Chapelle's third condition), most of them do not satisfy the first

principle because they do not require learners to generate their own sentences. This is

because speech recognisers work better in closed response designs (Ehsani & Knodt,

1998) which restrict learners to passive roles like reading aloud from written choices

(Berstein, 1994; Eskenazi, 1999). Under these systems learners have no practice in

constructing utterances on their own which is a major problem identified by a number of

researchers (cf. Eskenazi, 1999). However, such systems do allow learners to practise

example sentences. Under open response systems, learners can generate their own

expressions but the recogniser might not be able to rule out incorrect answers.

The second principle is also not fully met because the quality of feedback varies.

Encarta's Conversation activity gives no feedback. Language Connect and TeLL Me More only

allow learners to continue their conversations if their contributions are acceptable.

Users of the Virtual Challenge in Encarta Interactive English Learning can assess their

own performance by checking if they have successfully completed the assigned tasks. The

explicit feedback given by TRACI Talk is unfocused. However, there is also implicit

feedback provided by the user's ability to meet the challenge of obtaining essential

information by interacting with characters in the story. Most of the time, the programs

deal with unclear utterances by simply asking learners to repeat without indicating the

cause of the problem. More accurate feedback is needed for CALL because it will prevent

learners becoming frustrated or confused, and will assist them in improving their oral

English. The software reviewed here still needs to improve in this regard.

The third principle is generally met by these programs; they all provide a range of native

speaker models for learners to imitate. The fourth principle requires an emphasis on

prosody. While some of these programs offer spectrum as a visual feedback, the component

is not explicitly emphasized in most programs. To satisfy the fifth principle programs

should make learners feel at ease. A survey conducted at National Taiwan Ocean University

with students who had used TRACI Talk for more than seven weeks indicated that talking to

a machine reduced their anxieties in speaking a foreign language. They also found the

program intelligent and non-threatening. It seems likely that users of other software

would also feel at ease.

Conclusion

Clearly, the five commercial programs reviewed here can not provide all of the ideal

learning conditions recommended by Carol Chapelle (1998). The main problem is that to

allow learners to freely negotiate with computers is a daunting task for software

programmers because, as Chapelle (1998) points out, to engage in such a goal-oriented

conversation with natural language the program "would require more than language

recognition at the word and sentence level. It would require a 'knowledge base' about the

courses, schedules, and advising routines" (p.28).

Although these commercial products are far from perfect, they can facilitate second

language development. Their main advantages are that they: push learners to practise

and/or produce large quantities of sentences (either those provided by the CALL programs

or their own expressions); provide some pertinent corrective feedback; offer different

native models; and create a less threatening environment for developing speaking skills.

The potential of well-designed CALL programs which incorporate speech recognition

technology should not be underestimated by any language teacher.

References

Bernstein, J. (1994). Speech recognition in language education. Proceedings of the

CALICO '94 Symposium. pp37-41.

Chapelle, C. (1997). CALL in the year 2000: Still in search of research paradigms? Language

Learning and Technology 1(1), 19-43.

Chapelle, C. (1998). Multimedia CALL: Lessons to be learned from research on instructed

SLA. Language Learning and Technology 2(1), 22-34.

Chapelle, C. (1999). Investigation of authentic L2 tasks. In J. Egbert & E.

Hanson-Smith (Eds.) Computer-enhanced Language Learning. Alexandria, VA: TESOL

Publications. pp101-115.

Chen, H. (1999). Second language acquisition research and multimedia CD-ROM Evaluation. Proceedings

of the Eighth International Symposium on English Teaching. Taipei: Crane Publishing

Company. pp247-258.

Doughty, C. (1991). Second language instruction does make a difference: Evidence from an

empirical study of SL relativisation. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 13,

431-469.

Ehsani, F. & Knodt E. (1998). Speech technology in computer-aided language learning:

Strengths and limitations of a new CALL paradigm. Language Learning & Technology

2(1), 45-60.

Eskenazi, M. (1999). Using automatic speech processing for foreign language pronunciation

tutoring: Some issues and a prototype. Language Learning & Technology 2(2),

62-76.

Kenworthy, J. (1987). Teaching English Pronunciation. New York: Longman.

Larsen-Freeman, D. & Long, M. (1991). An Introduction to Second Language

Acquisition Research. London: Longman.

Long, M. H. (1996). The role of linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In

W. C. Ritchie, & T. K. Bhatia, (Eds.), Handbook of Second Language Acquisition.

San Diego: Academic Press. pp413-468.

Pica, T., Kanagy, R. & Falodun, J. (1993). Choosing and using communication tasks for

second language instruction. In G. Crookes & S. Gass (Eds.) Tasks and Language

Learning: Integrating Theory & Practice. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

pp9-34.

Swain, M. (1985). Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and

comprehensible output in its development. In S. M. Gass & C. G. Madden (Eds.) Input

in Second Language Acquisition. Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers. pp235-253.

Swain, M. (1998). Focus on form through conscious reflection. In C. Doughty, & J.

Williams (Eds.) Focus on Form in Classroom Second Language Acquisition.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp64-81.

Swain, M. & Lapkin, S. (1995). Problems in output and the cognitive processes they

generate: a step towards second language learning. Applied Linguistics 16,

371-391.