Catering for Individual Learning Styles: Experiences of Orienting Students in an Asian Self-access Centre

by Sue Fitzgerald, Andrew Morrall & Bruce Morrison

Contents: Introduction | Context | CILL | Learner Preparation | Orientation Process | Exploring CILL Program | Orientation Task Sheet | Tutor Talk | Questionnaire | Comments from Students & Future Development | Conclusion | References

Tables: Table 1 - Learner Preparation in CILL | Table 2 - Usefulness | Table 3 - Easy to follow | Table 4 - Confidence in using CILL

Reference: Fitzgerald, Susan; Morrall, Andrew & Morrison, Bruce (1996) 'Catering for Individual Learning Styles: Experience of Orienting Students in an Asian Self-access Centre' in AUTONOMY 2000: The Development of Learning Independence in Language Learning, Bangkok, Thailand; King Mongkut's Institute of Technology Thonburi, 55 - 69

It is generally acknowledged that, to facilitate personal growth and development, learners need to take a pro-active role in the learning process - generating ideas and learning opportunities rather than simply reacting to the stimulus of the teacher (Boud, 1988; Kohonen, 1992; Knowles, 1975). This has resulted in a shift, over the past decade, towards independent modes of learning and a consequent proliferation of self-access centres and independent learning programmes within the education sector. Within this educational context, there is a need for each institution to focus on the ideology and supporting methodology that is to guide its programmes and help develop in its learners the independent learning skills necessary for them to operate effectively.

Preparing the learner to study autonomously is an essential part of the philosophical and pedagogical framework of a self-access environment. However, individual learners differ in their study habits, motivation, and interests and develop differing degrees of independence throughout their educational career (Tumposky, 1982). It would seem appropriate, therefore, that any kind of learner training should take into consideration these factors at the design stage. In addition to individual learner differences, we must also consider cultural variations within the learning process which may cause resistance to the notion and practicalities of independent learning. Ho and Crookall (1995) suggest that the hierarchy of human relations in Chinese culture, and the respected position of the teacher, may cause difficulty for Chinese students, both emotionally and intellectually when encouraged to work autonomously. Independent learning can be seen as disempowering the teacher and encouraging the learner to defy previous learning experiences, thus challenging the view of the teacher as an unquestionable source of authority that is deeply rooted within Chinese culture. Based on the above, and in agreement with Dickinson (1987) we believe that not every learner will, or should choose to, be autonomous in their learning. Therefore, the learning training that a self-access centre provides should reflect this and provide as great a degree of flexibility as possible.

In much of the literature concerned with the development of learner autonomy, there is an emphasis on training the learner in terms of strategy development and learning skills (Dickinson, L. 1992; Ellis, G. & Sinclair, B. 1989; O’Malley, J.M. & Chamot, A.U. 1990; Oxford, R.L. 1990; Wenden, A . 1991). The physical aspects of learner training - familiarising the learner with the facilities and systems established within a centre, for example - have generally not been explicitly focused on to any great degree. This suggests that the basic skills that a learner in a self-access environment needs - such as identifying, finding and accessing materials, and keeping a clear record of work - should not be acquired in isolation but are to be learnt as part of a wider programme of independent learning strategy training. Holec refers to a "gradual deconditioning of the learner" (Holec 1980 quoted in Sheerin, 1991) which involves the learner in having to "re-examine all his prejudices and preconceptions" and redefine his entire approach to learning.

The orientation process described in this paper is an attempt to provide a flexible process which takes into account our learners individual differences while ensuring that they are equipped as fully as possible with the skills required to function effectively within an autonomous language-learning environment. In Hong Kong, a learner usually experiences a very traditional mode of learning in the years leading up to university entrance (Farmer, 1994; Ho and Crookall, op.cit). This, in addition to the constraints and pressure of university life, constituted the set of circumstances to be considered throughout the development of the Centre’s philosophy and the Centre itself. Every effort has been made to offer a variety of activity types, and a variety of learning mediums for learners at every linguistic level. In this light, we determined to take an approach in which our orientation process is viewed as the first part of an incremental, and individual-specific, development of autonomous learning skills.

This paper will describe the orientation process and the rationale behind its development. We will also comment on learner feedback on the orientation process and the impact this will have on the further development of the process.

The Centre for Independent Language Learning (CILL)

The primary aim of the Centre is to "facilitate the learning experience of our students using state of-the-art, innovative, learner-centred methodologies... and to encourage learners to take responsibility for developing their English language proficiency" (ref. Centre handout). We believe that a learner should be able to approach language learning in a way that takes account of their own language needs and learning style. Learners are expected to decide for themselves when to study, their pace of study, the level and type of materials that they use, and the type of learning tasks that they undertake.

The Centre offers a range of facilities (including multimedia computers with access to e-mail and the Internet, TV/VCRs, and audio cassette players for listening and pronunciation practice), and language learning materials.

All materials ( including CD-ROMs and videos) are on open-access and available directly to all learners. There is a tutor on duty throughout the day, whose principal role is to give help and advice to learners regarding the planning of learning objectives, and how to identify, access and effectively exploit, the materials in the Centre.

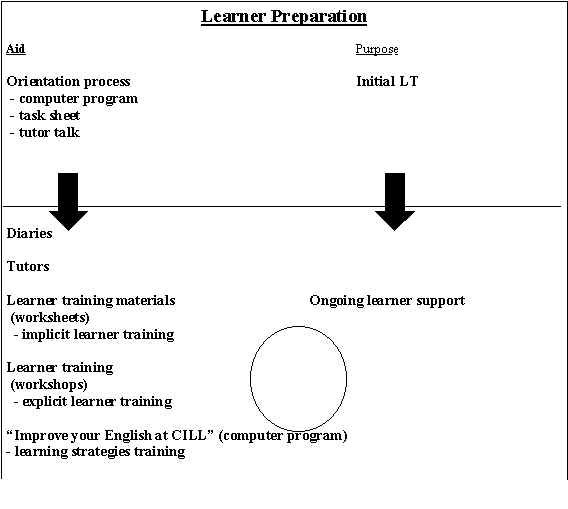

The initial orientation process described in this paper, together with ongoing learner support, comprise a holistic view of learner training that we have embraced and refer to as "Learner Preparation". The aim of learner preparation is to help our learners develop their individual autonomous learning skills.

Prior to registration in CILL, each learner is required to complete the orientation process. The ongoing learner support however, which comprises: learner diaries, help from a tutor, learner training worksheets, a learning strategies computer programme and learner training workshops is optional for the learner. It is important to encourage the learner towards independence by offering a variety of aids while also giving him the freedom to reject these and follow his own individual learning style.

Table 1 - Learner Preparation in CILL

|

The orientation process at CILL comprises three parts: a multimedia computer program ("Exploring CILL"); an activity which requires the learner to actively use materials in the Centre (Orientation Task); and a short talk with a tutor. The aim of the orientation process is to provide learners with the tools immediately necessary to operate within an independent language learning environment.

The Exploring CILL program, which was written in Asymetrix Multimedia Toolbook (CBT Edition), was designed primarily to offer an interesting and interactive mode for learners to discover some of the most important features of the Centre.

Our main concern when developing the program was the issue of navigation - both in terms of how the learner should navigate the program, and to what extent the learner should have navigational freedom. The literature suggests that learners are not normally able to take complete control of interactive computer programs without guidance in some format (Sciarone, A.G. & Mejier, P.J., 1993; Sorge, D.H. et al., 1994 ; Barnett, L., 1993). In an earlier, pilot version of the program, the learner entered directly into an interactive, map of the centre which gave the learner complete control of movement through the program by clicking with a mouse on hyper-linked "hotwords". However, it soon became apparent that learners were having problems with the program. Firstly, they were exiting the program too early - we felt one of the main reasons for this was the size of the program and the lack of guidance offered to the learner. Secondly, learners who were unfamiliar with computers did not understand the notion of (hot-word) hyperlinks between pages, and therefore did not take advantage of the full functionality of the program. In light of this, the decision was made to add a path through the program incorporating all the screens of essential information. Upon entering the program the user is presented with the first screen of the path and is only able to navigate forwards. After the first screen of information, the user has the ability to manoeuvre around the program by means of the clickable map, hyperlinks between related topics and through a contents page (Appendix 1). However, "Next page" buttons encourage users to follow the path further through the pages of essential orientation information .

The program includes a section on the importance of independent learning for learners in their studies and future careers, an introduction to the Centre’s academic and administrative staff, an overview of the Centre’s computer menu system and the materials labelling system (Appendix 2), the materials indexes, the role of the learner diary and other information learners need to use the Centre effectively. A short quiz to check the learners’ understanding of the Exploring CILL program automatically starts when the learners exit the program. Upon exiting the quiz, a button then takes the learner back to the main computer menu, or to a more detailed study skills program.

The second part of the orientation process is, as Sheerin (1989 ) suggests, a task sheet (Appendix 3) in which the tasks mirror the kinds of problem a learner might face when trying to use the Centre’s system. The tasks includes:

- using the indexes to identify potentially relevant materials;

- finding the materials on the shelves;

- understanding the materials colour-coding system for level and type of material;

- learning how to locate accompanying material (teacher’s book, cassette etc.);

- a ‘seven steps to effective study’ exercise.

The first question of the task sheet requires the learner to locate the indexes, identify an individual index, and to look for a specific topic area. The indexes are the key to enabling a learner to retrieve materials relevant to their learning objective. Without understanding how the index system works, an individual’s learning process may lack the focus necessary for him to identify relevant materials which could result in frustration and failure. The second question is a labelling activity which focuses on the index page layout. This activity is designed to familiarise learners with the elements of the index structure - including references to shelf location and unit number. The third question requires the learner to actually go to a shelf and locate a particular book, and name the title and page number of a given unit. This activity aims to consolidate the previous stage through the learner going through the process of physically locating a book. The fourth question focuses on the various parts of the classification labels. The labelling system in the centre is consistent for all materials including books, CD-ROMs, audio cassettes, videos, and worksheets. Every piece of material has a large, colour-coded label on its spine which contains information essential to the learner. The colour refers to the material type and shelf on which the material is stored. The other information relates to the level of the material, the type of material it is, and any accompanying material such as a cassette tape or workbook. The final part of the activity is, in effect, a strategy building activity which requires the learner to sequence seven suggested activities that would aid him in becoming more autonomous in their learning. This activity is then discussed in the tutor talk.

The third part of the orientation process involves the learner in a short talk with a tutor. The tutor checks that the learner has an understanding of the centre layout and material accessing system, in addition to providing some basic information such as opening/closing times, photocopying restrictions, etc.. The tutor also checks that a learner is aware of the CILL language level (Elementary, Early Intermediate, Intermediate, Upper Intermediate) that is most appropriate to their linguistic ability in each of the skill areas. This is determined by reference to the learner’s ‘Use of English’ examination score - an examination taken by students at the end of their secondary education.

The tutor then explains the role of two key elements of ongoing learner support within the Centre: the tutor and the learner diary. Both of these are designed to help the learner in the pedagogical structure of their learning program - in contrast to the role of the orientation process which is to enable the learners to exploit the facilities and systems within the Centre to promote effective independent learning. Learners are also encouraged to ask questions and identify materials which might be relevant to their University course of study.

As part of our initial attempts to assess how effective the orientation process is, a questionnaire (Appendix 4) was administered to one hundred and fourteen learners immediately after they had completed the orientation process. The questionnaire focused on three main areas: the usefulness of each section of the orientation process; how easy to understand each section is; and how confident the learner feels, after completing the process, about working independently in CILL..

The numbers in brackets refer to the percentages of responses (n=114)

|

|

These results suggest that students find the orientation process as a whole to be useful (88% found it "useful" or "very useful") and easy to follow (74% found it "easy" or "very easy"). What is interesting (although not entirely unexpected) is the high percentage of learners who felt that the section of the orientation process involving tutor participation - talking to the tutor, and the introduction to the learner diary - to be "useful" (45% and 47% respectively) and "very useful" (47% and 45% respectively). In contrast, the non-tutor involved part of the orientation was generally found to be "quite useful" (25%) and "useful" (59%). We could speculate from these results that learners find any activity involving a teacher to be more valuable for their learning, or that some learners are technophobic to a degree, or simply that students prefer the "human touch". Whatever the reasons, the mixed results support our initial decision to cater for individual learning styles by providing a variety of different media and approaches within the orientation process.

However, our findings from the third part of the questionnaire where the learner was asked how confident they felt about using the CILL without help after completing the orientation process, show that nearly half (46%) felt less than confident.

Table 4 - Confidence in using CILL

|

Thus, despite the positive feedback from the first part of the questionnaire, it seems that the process is not an unqualified success in its goal - although, it should be noted that 95% of respondents were at least "quite confident" about using the Centre. Among the various possible interpretations of these results, we feel that three factors are probably significant (the first two of which are reflected in some of the comments from students - see below): the CILL infrastructure is inherently quite complex and difficult to quickly internalise; the orientation process is not full enough; and individual tutor differences, in terms of both what they cover in the tutor talk and how it is covered. Additionally, the response may be explained by a degree of caution - with learners unwilling to express confidence before they have experience of actually using the Centre.

Comments from Students & Future Development

In the final section of the questionnaire, students were encouraged to comment on the orientation process. A number of interesting comments were made which will impact on future development. Initially, we have identified four of the comments which will guide the next stage of development - three specifically referring to the orientation process and one referring to learner access to materials.

It was suggested that there should be a video of how to use the materials in the Centre. We are in the process of making a video which introduces, not only how users can access the materials, but also an overview of the whole Centre and its systems - this video will be available in Cantonese, Mandarin and English to cater for individual student needs and preferences.

The second suggestion was that there should be more, and more detailed, advice from tutors on how learners can set achievable objectives. It should be noted that tutors do provide such information both throughout the learners programme of study and, if requested, during the orientation process. However, it has been decided to introduce a series of workshops that will help learners develop the metacognitive and cognitive skills needed to be an effective independent learner. These workshops would specifically address issues such as setting learning objectives, identifying relevant materials, deciding how to approach different task-types and note-taking. The orientation process does not provide such pedagogic guidance for two main reasons: firstly, there are severe time constraints both in terms of tutor availability and the amount of time a learner is able, or prepared, to spend on orientation; secondly, we feel that, since it would only be possible to present such guidance in the form of a brief overview, it would tend to add to the learners sense of information overload.

The third suggestion concerning the orientation process was that learners should be provided with a leaflet outlining details of the Centre’s systems (e.g. material labelling). We are examining the possibility of including such information in the learner diaries which would ensure that it was easily available to learners throughout their programme of study.

The suggestion referring specifically to material access - that learning "pathways" should be available to guide the learner through materials - was an idea that has already been considered. We are in the process of producing a number of "Learning Routes" which will suggest both different materials and different media that learners can use to consolidate a language area or topic.

The next stage in our investigation of the effectiveness of the process, will be to administer a questionnaire to the same learners after they have been studying in the Centre for some time and to follow up with some in-depth interviews. In doing this, it is hoped that we can more clearly identify aspects of the process that require modification.

The orientation process at CILL offers a practical introduction to the centre which enables the learner to engage in the learning process immediately.

It is an attempt to cater for a variety of learning styles, which are also reflected in the range of material-types and the physical design and infrastructure of the centre. It is intended that this variety also acts to motivate learners by encouraging them to experiment in their choice of learning materials and the way they approach them. Any "deconditioning", (Holec, op. cit) is voluntarily undertaken by the learner himself - an autonomous decision - rather than being imposed upon him by a programme of "learner training".

Barnett, L. (1993) Teacher off: Computer Technology, Guidance & Self-Access. System 21/2, pp. 295-304.

Barnett, L. & Jordan, G. (1991) Self-access facilities: What are they for? ELT Journal 45/4, pp. xxx.

Boud, D. (eds.) (1988) Developing Student Autonomy in Learning. New York: Kogan Page.

Brookes, A. & Grundy, P. (eds.) (1988) Individualisation and Autonomy in Language Learning - ELT Documents 131. London: Modern English Publications & British Council.

Dickinson, L. (1987) Self-instruction in Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dickinson, L. (1992) Learner Autonomy 2: Learner Training for Language Learning. Dublin: Authentik.

Dickinson, L. (1995) Autonomy and Motivation: A Literature Review. System, Vol.23/2, pp. 165-174.

Ellis, G. & Sinclair, B. (1989) Learning to Learn English. Cambridge: University Press.

Farmer, R. (1994) The Limits of Learner Independence in Hong Kong. In Gardner, D. & Miller, L (eds.) Directions in Self-Access Language Learning, pp. 13-27.

Gardner, D. & Miller, L (eds.) (1994) Directions in Self-Access Language Learning. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Geddes, M. & Sturtridge, G. (eds.) (1982) Individualisation. London: Modern English Publications.

Ho, J. & Crookall, D. (1995) Breaking with Chinese Cultural Traditions: Learner Autonomy in English Language Teaching. System, 23/2, pp. 235-243.

Knowles, M. (1975) Self-directed learning. New York: Association Press.

Kohonen, V. (1992) Experiential language learning: second language learning as cooperative learner education. In Nunan, D. (ed.), Collaborative Language Learning and Teaching, pp. 14-39.

Little, D. (1991) Learner Autonomy 1: Definitions, Issues and Problems. Dublin: Authentik.

Little, D. (1995) Learning as Dialogue: The Independence of Learner Autonomy on Teacher Autonomy. System, 23/2, pp. 175-181.

Nunan, D. (1992) (ed.), Collaborative Language Learning and Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Malley, J.M. & Chamot, A.U. (1990) Learning Strategies in Second Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oxford, R.L. (1990) Language Learning Strategies. Boston: Heinle and Heinle.

Reisman, S. (ed.) (1994) Multimedia Computing (506-535). London: Idea Group.

Sciarone, A.G. & Meilier, P.J. (1993) How Free should Students be? A Case from CALL: Computer-Assisted Language Learning. Computers and Education 21/1, pp. 95-101.

Sheerin, S. (1989) Self-access. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sheerin, S. (1991) Self-access. Language Teaching 24/3, pp. 153-157.

Sorge, D.H., Russell, J.D. & Weilbeaker, G.L. (1994) Implementing Multimedia-Based Learning. In Reisman, S. (ed.) pp.506-535.

Tumposky, N. (1982) The Learner on his own. In Geddes, M. & Sturtridge,G. (eds.) Individualisation. London: Modern English Publications pp. 4-7.

Wenden, A. (1991) Learner Strategies for Learner Autonomy. UK: Prentice Hall.

Wenden, A. and Rubin, J. (1987) Learner Strategies in Language Learning. Cambridge: Prentice Hall.